For some reason I woke up this morning thinking about days. We divide our lives into measurable units – years, months, days, hours – and each passing day has a character or identity of its own. Each day in itself, a microcosm of life: we die each night and are reborn each morning. And there are so many days! In my life so far, up to and including August 13th 2022, there have been 25,792 days. This includes extra days for leap years.

In the grand scheme of things, Planet Earth is very small – according to Carl Sagan: a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. And, in the grand scheme of things, a single human life is very small indeed. Google informs me that, including the current world population of 8 billion, 117 billion people have lived and died over the course of 192,000 years - which makes a single day in a single life infinitesimally small.

Fortunately, we do not weigh our days against this wider perspective. We are selfish, creatures, living in

Philip Larkin, in his poem ‘Days, poses the question What are days for? and gives his answer: Days are where we live. they wake us / Time and time over. / They are to be happy in: / Where can we live but days? There are two schools of thought about the days that make up a human life: the idea that each day is wonderful and a cause for celebration and the idea that each day is meaningless and absurd.

A classic example of the pessimistic point of view is Macbeths speech which begins: Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day, / To the last syllable of recorded time. In other words, days are mere on the road to death. A similar view is taken by Jacques Prvert in his poem ‘Dejeuner du Matin, where the speaker is appalled by the banality of everyday existence and bursts into tears at the breakfast table. And perhaps the most extreme example of the idea that every day is something to be endured is

Given terrible circumstances, it is indeed possible to feel as Estragon does. I am not so sure, though, about the man in the Prevert poem. The banality, the mindless routine, he rails against could equally be interpreted Many people, myself included, enjoy familiar routines. If every day were a voyage into the unknown, it would be too much; I can stand only so much adventure. My day always begins with a plate of fresh fruit and a mug of Indian tea, enjoyed while checking my email and the world news. My days always end with banana wine and online chess.

My general view is that life is all weve got – there is no – so we have to make the best of our days under the sun. As those great philosophers, Crosby Stills and Nash, said: Rejoice rejoice, we have no choice / But to carry on.

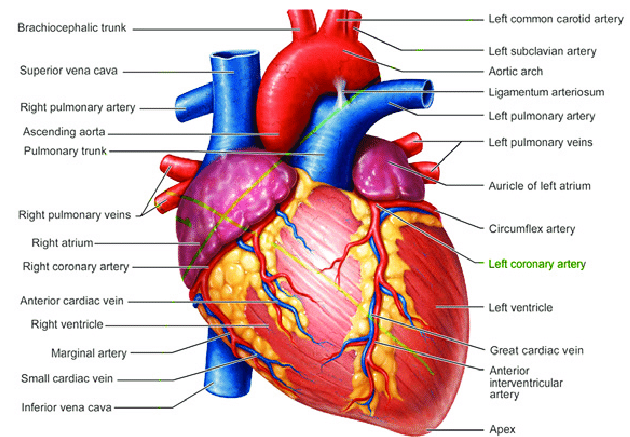

Going back to the sheer number of days in a single human life, I am struck by how amazingly robust the human body is. The simple fact that it can

function for – in my case – 70+ years is remarkable. My heart has been beating for 25,792 days – a total of approximately 25,792 x 1440 (minutes in a day) x 70 (heartbeats per minute) heartbeats. to 2,599,833,600 – over 2.5 billion. And then there are the number of breaths I have taken, the number of meals I have digested, the number of times I have urinated and defecated, the number of steps I have taken

Even more remarkable are the workings of the human brain. In a single day, imagine all the thoughts and emotions that it processes – all the decisions taken, all the words spoken and read. Then multiply that by 25,792. Specks of dust we may be in the context of the Universe, but the human body is a perfect machine, performing multiple functions automatically, and the human brain is the thing yet discovered. Working in harmony for 25,793 days, my body and brain have given me an incredibly rich life.